The largest known muskie is 67 pounds 8 ounces. Or it’s 69 pounds 11 ounces. Or it’s 70 pounds 10 ounces. Depending on the type of record, whom you ask or what organization you trust, it could be any of those answers.

After Great Lakes Now published a column on muskies that referenced record sizes, it kicked off a dispute among readers on what record was the most accurate, so Great Lakes Now decided to do a deeper dive.

Tough catch

Muskie are known as the fish of 10,000 casts due to their skill in avoiding fishhooks. So, it stands to reason that catching the world’s largest muskie is an achievement that many sportsmen would like to attain.

But when it comes to record-setting fish, there are a number of factors that need to be taken into consideration before bestowing any titles.

For a start, length and weight are the two common measures used to gauge a fish’s size. But if the longest fish is not the heaviest fish, which one takes the world record for largest?

For natural history museums like the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, both measures are award worthy.

Erling Holm is a curator in the department of ichthyology at the Royal Ontario Museum and lead author of the ROM Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of Ontario. As a fish scientist, Holm is interested in the record for both maximum length and maximum weight ever documented.

Holm said the website Fishbase.org is a reliable depository of fish records and the source for the muskie world records for length and weight listed in the ROM guide.

FishBase hosts the most comprehensive database of fish species available online. The website features a user-friendly search option that allows visitors to access fish data by common name, preferred habitat, global watershed, and dozens of other filters including by world records.

For muskies, the world records for length and weight are held by two different fish. The maximum documented length is 72.04 inches (183 cm), and the heaviest documented weight is 70.10 pounds (31.8 kg), according to FishBase.

Holm notes that world-record fish are not always caught by sportsmen. Record-breaking fish are often caught or found by researchers, commercial fishers and amateur naturalists. Some are even specimen that wash up on the beach.

But while museums may be interested in the longest and heaviest examples ever documented, in sportfishing it’s all about the weight.

Sgt. Mark DePew with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources law enforcement office said sportfishing records are almost always awarded to the heaviest fish. The desire to catch the weightiest fish has occasionally led some anglers to try unscrupulous tricks.

DePew said most sportsmen are honest, but some have been caught trying to make fish heavier by stuffing them with lead weights or by pouring sand or water down their throats.

A winning fish can earn thousands in tournament cash prizes. A record-setting fish can gain the angler fame and possible sponsorship from fishing manufacturers. And a world-record fish can generate a lot of revenue for businesses in the surrounding area.

“There’s a real dollar figure that is tied to these big fish,” DePew said.

Verifying the catch

With every state and world-record-setting sportfish that is caught, bragging rights, lucrative sponsorships and tens of thousands in tourism dollars are also on the line, which is why every potential record-setting catch must undergo a gauntlet of scrutiny to earn and retain a title.

The first step in the process is to get the fish weighted on a recently calibrated commercial scale said Jan-Michael Hessenauer, a research biologist with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

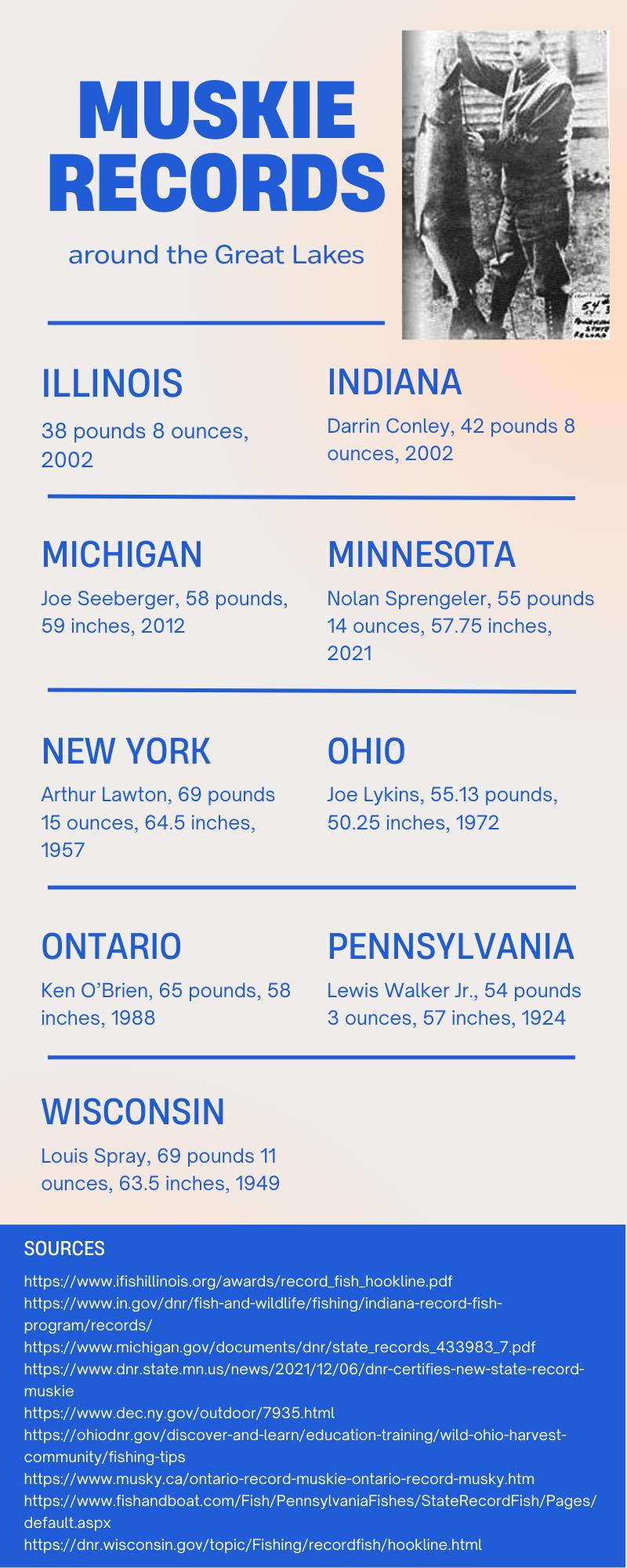

Muskie catch records around the Great Lakes by state and province. (Graphic created by Natasha Blakely/Great Lakes Now)

The Michigan DNR requires a research biologist witness all weigh-ins for state records.

The DNR biologists also check for signs of illegal activity such as artificial weight from sanding. They will confirm the fish is a fresh catch and does not show signs of being held captive like in a pen, and finally they will make sure it is a legal catch.

Hessenauer works out of the Mt. Clemens Fisheries Office on the shores of Lake St. Clair. If a record-breaking muskie is caught in Lake St. Clair, Hessenauer is most likely to be called to verify the catch. He has yet to receive a request.

“State record-sized fish are rare,” he said.

The Michigan DNR website has a downloadable application and step-by-step instructions on how to report a record-setting fish.

Each state maintains a list of fishing records. Around the Great Lakes, state records for muskie range from a low in Illinois of 38 pounds 8 ounces to a high in New York of 69 pounds 15 ounces.

The verification process for a world-record muskie involves an even higher degree of scrutiny than state record holders. And while the organizations providing that scrutiny have changed several times in the past century, the level of examination each fish undergoes has only increased.

The Record Keepers

In the early 1900s, the American Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C. and Field & Stream Magazine began recordkeeping programs for sportsmen. When the Natural History Museum terminated their recordkeeping program, they relinquished all their records to Field & Stream.

In 1939, the International Game Fish Association was founded.

Field & Stream and the IGFA maintained similar but independent recordkeeping programs for 40 years. But while these organizations recognized a few freshwater world records, the vast majority of their efforts were focused on saltwater records for more lucrative species like marlin and swordfish.

In 1976, the Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame opened in Hayward, Wisconsin. In addition to a large exhibit dedicated to Great Lakes angling and muskie in particular, the museum also launched their own world record program focusing strictly on freshwater sportfish.

Two years later, Field & Stream decided to terminate their recordkeeping program and relinquished all their records to the IGFA. In the November 1981 issue of Field & Stream, editor Duncan Barnes reports that this records merger was done with the goal of eliminating confusion over world records and to consolidate all fishing records under “one roof.”

International Game Fish Association logo

In 1980, a final recordkeeping consolidation occurred when the Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame agreed to transfer all their records to the IGFA so they could “serve as the single universal source for such information,” according to Barnes’ 1981 editorial.

The IGFA website states that by the end of 1980 the international association had accepted more than 150 new fishing class records and 20 fly records into the freshwater category.

Incorporating the Field & Stream records into the IGFA program was accomplished smoothly and efficiently but reconciling the Freshwater Hall of Fame’s records proved far more problematic for the IGFA.

Elwood K. Harry, president of IGFA at the time of the Hall of Fame records merger was quoted in Barnes’ 1981 Field & Stream editorial, calling the Hall of Fame’s records “inaccurate and quite obsolete.”

“Our studies have clearly shown that over the years, grave errors have been made by the hall in species identification, weights, and methods of catch. We have diligently gone through all the Hall’s records and eliminated those that were not properly documented and replaced others for which the investigative data was not up to our high standards,” Harry said.

The Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame took exception to the IGFA’s assessment of their records, and in 1981 the hall resumed their independent world recordkeeping program.

Barnes concluded his 1981 Field & Stream editorial by stating “the American Fishing Tackle Manufacturers Association recognizes and endorses the IGFA as the sole keeper of all official saltwater and freshwater angling records. So do knowledgeable anglers throughout the world. And so does Field & Stream.”

Today, the IGFA and the Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame both maintain sportfishing recordkeeping programs, and they disagree over who holds the world record for the largest muskie ever caught by hook and line.

The title holders

Calmer “Cal” Johnson was a well-known and prolific outdoor writer in the early part of the 1900s. He worked as editor for both Outdoor America and Sports Afield magazines, had a radio show that reached thousands of listeners and, according to a website about Cal Johnson, he also directed fishing trips for Presidents Coolidge and Hoover.

On July 24, 1949, Johnson claimed to have caught a 67-pound 8-ounce muskie on an inland lake near Hayward, Wisconsin. Photos were taken, witnesses watched the weigh-in, and Johnson submitted his catch to Field & Stream as a new world record.

However, before Field & Stream was able to complete the verification of Johnson’s application, an even larger muskie was caught and Johnson’s catch was relegated to second place.

Alton Van Camp, friend of Louis Spray, holding Spray’s 59.5-pound muskie. (Photo Credit: Wisconsin Historical Society)

On Oct. 20, 1949, Louis Spray produced a 69-pound 11-ounce muskie he claimed was caught in the Chippewa Flowage also located near Hayward, Wisconsin. No photos were taken of Spray holding the fresh catch and there was some discrepancy with the weigh-in, but Spray still submitted his catch to Field & Stream as the new world record.

Almost immediately rumors began to circulate questioning the legitimacy of Spray’s catch, according to Larry Ramsell who developed the recordkeeping program for the Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame and was an IGFA representative for 16 years.

In his book, “A Compendium of Muskie Angling History Vol I,” Ramsell argues that Spray’s reputation as a bootlegger and businessowner willing to purchase illegal fish catches were grounds to question his world record claim.

Ramsell points to the absence of any photographs showing Spray holding the alleged record-setting fish as further support of the claim that Spray purchased rather than caught the big muskie.

Regardless of the rumors, Field & Stream reviewed and approved Spray’s application, and his catch became the world record holder for largest muskie caught by hook and line.

Spray’s world record went unchallenged for only eight years.

In 1957, Arthur Lawton claimed to catch a 69-pound 15-ounce muskie while fishing in the St. Lawrence River, breaking Spray’s record by just 4 ounces. Photos were taken, witnesses watched the weigh-in, and Lawton submitted his application to Field & Stream as a new world record.

Field & Stream reviewed and then recognized Lawton’s catch which went unchallenged for almost 20 years.

John Dettloff is the board president of the Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame and author of “Three Record Muskies in His Day, The Life & Times of Louie Spray.” Dettloff doubted Lawton’s catch and claimed a non-professional photographic review proved that Lawton’s muskie was not as large as reported.

The Hall of Fame petitioned the IGFA to re-examine Lawton’s claim, and in 1992 after an extensive review process using modern photographic analysis the IGFA set aside Lawton’s catch and the world record reverted back to Spray and Hayward, Wisconsin.

However, some members of the muskie community argued that in fairness Spray’s claim should also have to undergo the same updated level of scrutiny as Lawton’s fish.

The IGFA agreed, and after another intensive review process the IGFA decided to also set aside Spray’s claim. With Lawton and Spray’s catches no longer in contention, Cal Johnson’s fish became the new IGFA world record holder for muskie.

A fiberglass-and-steel muskie sits outside the National Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame in Hayward, Wisc. (Photo Credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Carol M. Highsmith [LC-DIG-highsm-16714])

The Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame in Hayward, Wisconsin, disagreed with the IGFA’s decision and continued to promote Spray as the world record holder. Lack of consensus amongst these recordkeeping organizations created discourse within the muskie fishing community.In January 2004, the World Record Muskie Alliance was formed with the goal of finally reaching a consensus on the muskie world record holder. The non-profit group was comprised of muskie anglers and experts who believed the controversy over the legitimacy of the muskie world record could be unraveled through the application of modern technology and unbiased investigation methods, according to the organization’s summary report.

To conduct the scientific review, the Muskie Alliance hired Dan Mills, a former surveyor and Transport Canada inspector who reconstructed highway accidents and analyzed photographs to determine the height of crime suspects. Mills applied modern forensic techniques to the only known photos of Spray’s muskie.

The study results were published in 2005. The Muskie Alliance review determined that the muskie in the Spray photographs was smaller than claimed.

Unfortunately, the Muskie Alliance report did not unify the community as hoped.

Currently, the New York DNR continues to recognize Lawton’s catch as the world record. The Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame and the Illinois and Wisconsin DNRs recognize Spray’s fish as the record holder. The IGFA awards the world record title to Johnson’s muskie. And online sportfishing forums and comment sections are brimming with contradictory assertions regarding who is the rightful title holder.

The world records for longest and heaviest muskie ever documented and the largest caught in each state are generally accepted.

But the award and corresponding fame for catching the world’s largest muskie by hook and line remains a hotly contested controversy that, after nearly a century, can still ignite a lively debate in comment sections and online forums.

I Speak for the Fish: Meeting the mysterious muskie

Top 10 Fish to Catch: Great Lakes means great fishing

Featured image: Alton Van Camp, friend of Louis Spray, holding Spray’s 59.5-pound muskie. (Photo Credit: Wisconsin Historical Society)

0 Comments 1 Likes