The following talk was delivered at the Bennington Writing Seminars Commencement Address on January 15, 2022.

*

Dear Writers. Dear Graduates:

Everything about my presence here seems unlikely. This tangle of wires and chips and Bill Gates’ dubious imagination I’m speaking into has gotten me from here to there, and you from there to here. Somewhere in the space between Southwest Michigan and wherever you find yourselves, I touch your hand.

Yes, I’m from rural Michigan. My people are those of TV dinners and bad luck. My landscape, silos, pissed-off cows, and the Elks Lodge Friday Fish Fry sign lighting up the night instead of the moon. My high school was in a cow pasture. It was a loamy soil for future poem-making, but not a place to learn the mechanics of poetry. It was a place to learn auto mechanics and home economics—how to bake banana bread while replacing the carburetor. Those are crucial skills. They served me well.

I did go to college, but mostly while there I was up to no good. I think I vacuumed up just what I needed to know—and no more. A class called “Modern Poetry.” Another called “Modern Art History.” And one called “Human Biology,” which came in handy when I had a urinary tract infection.” Mostly, during those years, I invented myself, or a version of myself that could resurrect out of a cow pasture and become a poet. Unlikely, unlikely that I am here at all, and that you, indeed, are there.

If I were with you in the real—real life, real time—I’d want to hear each of your stories about your own unlikeliness, about how you ended up in the program, and what you made of your time there, what you read, who you loved, what irked and nettled you, what mattered to you, what made you recoil. I’d want to hear your work. I’d want to look down into whatever well or bottomless pit you drew it up from. To be embodied together, en-storied together, now seems as unlikely as a fairy tale, or a dream. Have we learned our lesson yet? About embodiment? About stories? Our need for connection in order to tell them? Our need for a usable past? I have been, in my time, a wanderer, a kind of picaresque character of my own design, but also a person who courted loneliness, with a hermit’s imagination.

In the last line in one of the last sonnets in my most recent collection of poems, I write: “That loneliness I lusted for, I have become.” Not “I feel lonely” or “I am in a state of loneliness,” but I am loneliness itself. “It might be lonelier without the loneliness,” Emily Dickinson writes, getting at the companionability of it all, loneliness, the idea of it, separate from her but of her, hers. Yes, loneliness has been my cry, my charge, my aesthetic, my bedmate. But after the last two years, I want to give up, give in. Choosing solitude is one thing. Having it foisted on us, by fate, by tyranny and ignorance, is quite another. Now, now, I want nothing more than to connect. And that want has led me to think about connection, the wish for it, the demand for it, in writing.

I wish you solitude, yes, but also loneliness, the aching, fruitful kind.I want to say for you my favorite poem, which I think may hold a key to what you may have signed up for, in embarking on and completing this degree. It is barely a poem, just eight lines. It was written in the midst of a longer poem Keats was working on at the time of his death at age 25 from tuberculosis, in Italy, where he’d gone on doctor’s orders to escape the English damp and cold. Now I’m quoting Edward Hirsch on Keats’ situation, and what led him to this poem:

Keats had received his death warrant from tuberculosis, and the great poems were behind him—the sonnets, the odes, including “To Autumn,” which may be the most perfect poem in English. He was working on a comic poem to be called “The Cap and Bells; or, The Jealousies.” He never finished the fairy tale, the weakest of his mature poems, the Spenserian stanzas he churned out with remarkable fluency to earn some money for his publisher, but at some point, while he was writing it, he broke off and jotted down some lines in a blank space on the manuscript. He turned from stanza 51—”Cupid I / Do thee defy”—and wrote something dark and serious, preternaturally alive, this untitled eight-line fragment:

This living hand, now warm and capableOf earnest grasping, would, if it were coldAnd in the icy silence of the tomb,So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nightsThat thou would wish thine own heart dry of bloodSo in my veins red life might stream again,And thou be conscience-calm’d–see here it is–I hold it towards you.

This is a poem written from the very edge of death, from the seam of the shroud. “This living hand,” he begins, announcing from the first phrase that as he writes, he is alive: “now warm and capable / of earnest grasping.” Now, right now, warm, capable, but “if it were cold,” and that coldness is coming, he knows it, “and in the icy silence of the tomb,” and hear how “icy” and “silence” speak to each other in those long “I” sounds, that cold hand would “so haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights,” he writes, putting a kind of curse on you, on me, the haunting of the cold disembodied hand, “That thou would wish thine own heart dry of blood / So in my veins red life might stream again / And thou be conscience-calm’d.” It’s poem-as-vampire. You would, if he were in the icy silence of the tomb, and he will be of course, he knows it, soon, want to give him your own blood, your heart’s blood, so he would live again, and your conscience would be calmed.

So, what is this blood he’s demanding of you? I believe we learn that in the ferocious little poem’s final lines: “see here it is— / I hold it towards you.” Here it is, he writes, he speaks, and in the moment of the poem’s writing, via the vehicle of the poem itself, he holds his very hand towards you. You. You, reader. His actual hand, once warm, now cold and in the icy silence of the tomb. Through time. Through space. Through the very page. Through tangled wires and microchips there it is. His hand, waiting for the lifeblood of your attention. He wants what all writers want, what all people want I imagine. Read me. Take my hand.

Whitman, at the end of “Song of Myself,” writes a similar missive to you, though with a very different tone.

I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles.

You will hardly know who I am or what I mean,But I shall be good health to you nevertheless,And filter and fibre your blood.

Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,Missing me one place search another,I stop somewhere waiting for you.

If you want me, I’m right there under your boot-soles, as he has bequeathed himself, his very body, to the dirt, to the grass. “I shall be good health to you,” he writes, “And filter and fibre your blood.” Wow. Vitamin Walt. “Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,” he writes, egging you on, egging on the reader through the poem. You don’t get it? he might say. Keep going. “I stop somewhere waiting for you.” He waits for me, for you. Not in the clouds but here, on the earth. He wants what? Our attention. Our willingness to connect over time and space. Here I am. I defy death. I hold myself, via the poem, toward you.

Miklós Radnóti, a Hungarian poet, was drafted into hard labor in a copper mine in Bor, Yugoslavia during World War II. This, again, is from Ed Hirsch:

He was taken from the mine and driven westward across Hungary in a forced march, and there, near the town of Abda sometime between November 6 and November 10, 1944, he became one of twenty-two prisoners murdered and tossed into a mass grave by members of the Hungarian armed forces. It was an unspeakable death. After the war, Radnóti’s wife had his body exhumed, and his last poems were found in his field jacket, written in pencil in a small Serbian exercise book, which is now known as “The Bor Notebook.” These poems literally rise from the grave to give testimony.

Here is the last of those poems, just seven lines, which he called “postcards.” There is a line he writes in German here, but I will read it in English lest I mangle it:

I fell next to him. His body rolled over.It was tight as a string before it snaps.Shot in the back of the head—“This is howyou’ll end. Just lie quietly,” I said to myself.Patience flowers into death now.“That one is still twitching,” I heard above me.Dark filthy blood was drying on my ear.

Radnóti writes prophetically, or in the midst of, his own execution. His body is his witness. He sends a postcard from death itself to be discovered, mysteriously, dizzyingly, by the future. How brutal. How transcendent. My friend Mikel, who died of AIDS in the mid-1980s, told me that if he had it to do over again, he would paint himself right into the grave. I’m sorry to be gruesome, but these are gruesome times. We must look that reality in the eye before we can claim the power of this thing you wield as a writer. The power to resist, to defy, death. This pen.

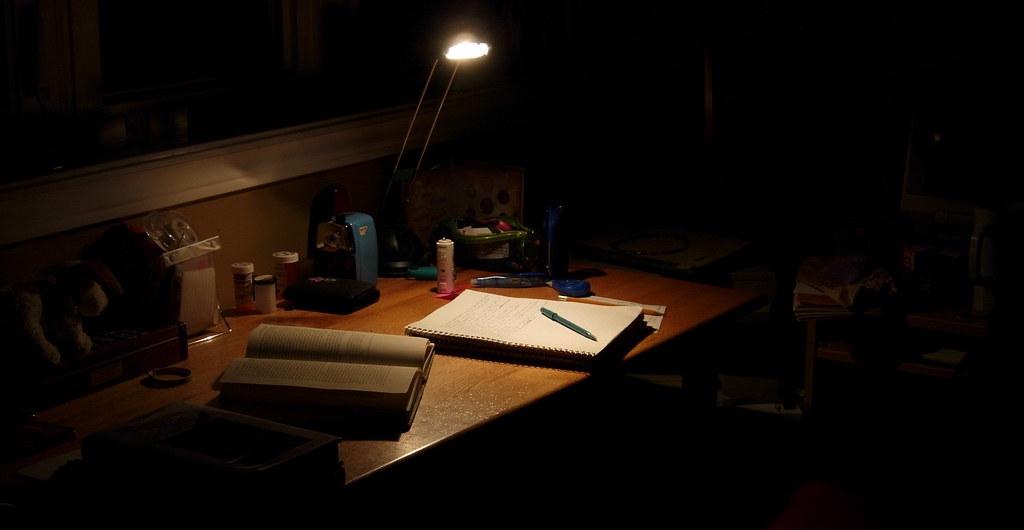

If I were able to be with you today, I’d ask you what first drew you to the writing life. I’d want you to tell me how it all started for you—what instigated the urge. I imagine for some of you it was some kind of emptiness, the lack of a place in which you could be yourself, a trauma, an unmet hope or need or desire. Maybe you felt estranged from your peers, estranged from conventional uses of language. Maybe you read books under the covers with a flashlight in bed. Maybe you dreamed of blue hummingbirds in the trees, that the trees were blurry with them, but no one but you could see them. Maybe you went to church but you just couldn’t feel it when they said you were saved.

For me, writer, listener, it was this: I was raised in a village with a dirt main street. I wandered early, probably long before children should wander. We lived next to the village cemetery, a very cool and creepy place with woods on one side, a field with horses on another, cordoned off from the graves with a barbed wire fence, and a bog on the third. There was a cave on the bog side where they stored the bodies in the winter, when the ground was too cold for the gravedigger to do his job. Every day, rain, shine, or snow, a woman walked by our house wearing a long black coat, black four-buckle boots, and a black hat with a veil. She’d turn down cemetery lane to go talk to her dead, including her fiancée, who died in war. The walk from her dilapidated farmhouse far outside the village was miles.

My father was still alive then, but the first symptoms of what would be his fatal illness, that took him when I was seven, were beginning to appear. I myself had a small wooden crutch he’d made me after a leg injury, but I followed her, down the pine-bordered lane, to listen-in, if I could hear her, and if not, to watch the movement of her lips through the veil as she made the connection—or tried to—with her dead. A connection that had to be revived daily, and was worth walking miles to maintain. For me, writing arose out of the same urgent need, to connect with my dad, once he was gone, and with ancestors I never knew, and ultimately, through reading, with those scribblers who came before me, and finally, especially now, through writing, with those who I can only imagine, future readers to whom I extend my hand, demanding the lifeblood of their attention.

In the last poem of my most recent book, frank: sonnets, I envision the literary lineage through kisses. Here are its last lines: “I kissed lips that kissed Frank’s lips though not / for me a willing kiss I willingly kissed lips that kissed Howard’s death bed lips I / happily kissed lips that kissed lips that kissed Basquiat’s lips I know a man who said / he kissed lips that kissed lips that kissed lips that kissed lips that kissed Whitman’s / lips who will say of me I kissed her who will say of me I kissed someone who kissed / her or I kissed someone who kissed someone who kissed someone who kissed her.” For those of us who arise from the margins, who are marginalized, to consider oneself as part of the human lineage, the lineage of literature is, in itself, a dizzying leap of the imagination.

I wish you a sexy, dangerous, jazz-shaped immortality.The first college class in which I read a woman writer was called, blatantly enough, “Women’s Literature.” What I remember most was that the professor used the term, in teaching Toni Morrison’s Sula, “downward transcendence.” Theorist Helene Cixous writes that paradise is below. To reach it is a matter of descent, not ascent. “Giving oneself to writing means being in a position to do this work of digging, of unburying, and this entails a long period of apprenticeship, since it obviously means going to school. Writing,” she says, “is the right school.” Cixous’ father died young, of tuberculosis. Her mother then became a midwife who delivered “hundreds and hundreds” of babies.

This is the border Cixous writes from, the border between birth and death. “Our lives are buildings made up of lies,” she writes. “We have to lie to live. But to write we must try to unlie. This requires courage… When I write I escape myself, I uproot myself, I am a virgin; I leave from within my own house and I don’t return. The moment I pick up my pen—magical gesture—I forget all the people I love; an hour later they are not born and I have never known them.” In other words, she estranges herself.

And so, graduators, writers, you commenced on this calling, this affinity, long before you entered the program, and you will continue commencing after you receive your degree and throughout this puppet show we call a life, much of which you will build through the strange architecture of language. Something knocked on your door early. Somehow, Little You had the courage to answer it. Through the years of this part of your formal education, you descended, and with Kafka, at one time or another you might have said, or felt, “What a place! It is probably the deepest place there is. But I still stay here, only do not force me to climb down any deeper.” Yet deeper you have gone, and deeper you will go still. Kevin Young, tired of hearing critics bark that poetry is dead, writes, in his essay “Deadism”:

For years I felt poetry was not ceremony, but the daily thing. The dirt. It is an everyday, not an occasionally. I still think it is. But perhaps the only way to make this truly true is to write a poetry that is not like death, but is death: surprising yet inevitable, everyday yet far-off in the future, an ever-present that we still manage to forget. In this, it may resemble jazz — or is this simply because, as Ralph Ellison says, “’life is jazz-shaped”?… Maybe what we need is an undead poetry — not to take death back from poetry, but to take death back from death itself. A poetry of shambling power, devouring everything it its path. A vampire poetry that will live forever, sexy and dangerous and immortal.”

Commencers, I wish you a sexy, dangerous, jazz-shaped immortality. I wish you the touch of the hand of the dead through the page; I wish you the will, the courage, to resurrect them via your attention. The guts to deconstruct the lies. I wish you a daisy chain of memorable kisses that link you back to your ancestors, and forward to those writers you can barely imagine. I wish you the power of the threshold, the page that, as Gregory Orr has written, is shaped like a doorframe that stands at the seam between disorder and order, death and life. I wish you solitude, yes, but also loneliness, the aching, fruitful kind. And somewhere up ahead all of us, all of your teachers, will be waiting for you.

Thank you for the gift of your attention, and congratulations.

Diane Seuss

Diane Seuss is the author of frank: sonnets, Still Life With Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, Four-Legged Girl, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and Wolf Lake, White Gown Blown Open, winner of the Juniper Prize. She lives in Michigan.Previous Article

Oscars Best Picture Spotlight: What to Read (and Watch) If You Liked Drive My CarNext Article

Lit Hub Daily: March 21, 2022Bennington Writing SeminarsBennington Writing Seminars Commencement AddressDiane Seussfrank: sonnetspoetry